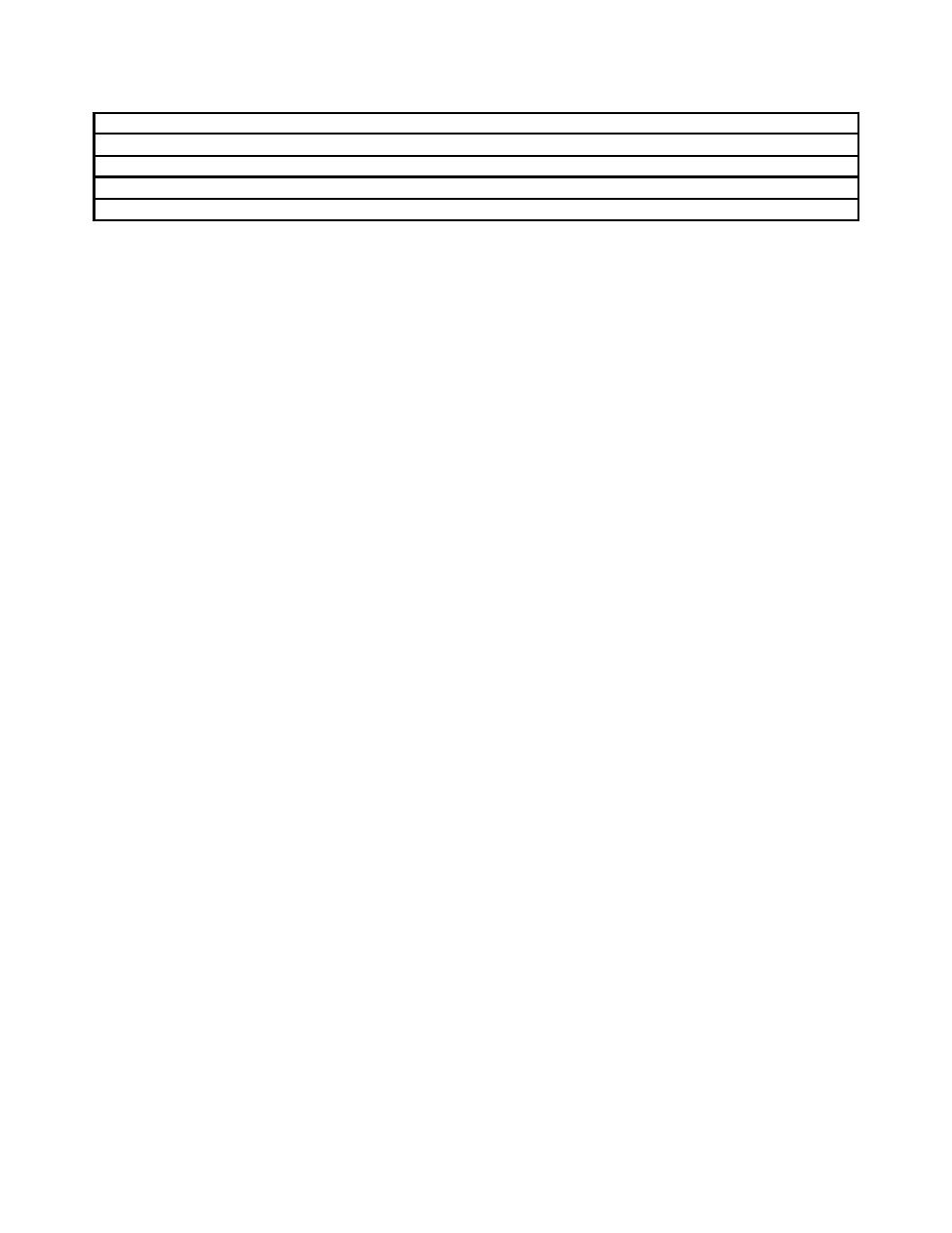

B

Paul

Affairs of

c Shall make known.

b Whom I have sent.

c

Ye might know.

a Our affairs.

A

Benediction All who love (panton ton agaponton).

What is Ministry?

There is an intimate connection between the ministry for which Paul asks

prayer, and his affairs which he makes known through Tychicus. We are apt to

limit our conception of ministry too closely to the actual work of speaking or

writing. Were not Paul's private affairs a part of his ministry? Had not his

prospects been ruined for the truth's sake? When he sometimes laboured with his

hands to provide the necessary things of life could he not render that humble

service as unto the Lord? When the Philippians sent once and again unto his

necessities, did they feel any need to distinguish between the sacred and the

secular? Was it not at the same time fellowship in the gospel? (Phil. 1:5;

4:15,16). Ministry is simply service, and this includes the whole of life, for

often the demands of the ministry, rendered seriously, deflect the whole current

of daily affairs. So it is that Paul could link together the high ministry of

the Mystery and `how I do' without any feeling of incongruity.

Prayer expresses a sense of need

His prayer was for `utterance', `boldness', the ability and the courage to

speak freely as he `ought'. Here is a man of like infirmity as ourselves. He

knew what it was to feel a shrinking, and could sympathize with the timid spirit

of Timothy (2 Tim. 1:4,7). He knew what it was to be despised (2 Cor. 10:10),

and to have indifferent health (Gal. 4:13,14). He knew that whenever there is

an `open door' there will be `many adversaries' (1 Cor. 16:9), and prayer was

needed that the opposition would not be allowed to turn him back from the

appointed path. Did he never have moments of doubt when, with aching limbs and

tired brain, he laboured and travailed at some lowly occupation for the bare

necessities of life? Did no one whisper that he might have served the Lord

better by staying in honour and influence at Tarsus? Did he never need the

vision at night of the Lord saying:

`Be not afraid, but speak, and hold not thy peace: For I am with thee, and

no man shall set on thee to hurt thee: for I have much people in this

city' (Acts 18:9,10).

Unless we have made a most critical mistake in our understanding of Paul's

temperament and circumstances, we believe he had the scholar's shrinking from

the physical blow, the supersensitiveness to criticism, the knowledge within of

his own utter unworthiness, the consciousness that in following his calling he

must ever appear in the eyes of many as a presumptuous boaster. Yet he turned

not back. This man who shrank from the tumult of Corinth was ready to face the

mob at Ephesus (Acts 19:30), or the enraged Jews at Jerusalem (Acts 21:40). He

could write to the Philippians:

`That with all boldness, as always, so now also Christ shall be magnified

in my body, whether by life, or by death' (Phil. 1:20).

He could speak of himself as a drink offering poured out upon the

sacrifice and service of faith (Phil. 2:17). There is some compensation to the

sensitive spirit, if he or she `suffer as a Christian', but Paul had to face the

342