DISPENSATIONAL TRUTH

By Charles H. Welch

Hope. While there are a number of Hebrew words translated "hope" in the O.T., there is but one basic Greek word so translated in the N.T. It will not be possible to examine the references in the O.T. in detail, but it will give us some idea of what "hope" meant in the days of old if we (1) examine the different Hebrew words used, and (2) note what Hebrew words are translated elpizo or elpis in the LXX.

- Betach. "Therefore... my flesh

also shall rest in hope" (Psa. 16:9). This word means: to cling as a

child to its mother's breast (Psa. 22:9), and to trust, to rely upon,

and then to be confident.

- Batach, the verb, is translated

mostly "trust".

- Kesel. "That they might set

their hope in God" (Psa. 78:7). The radical idea of this word is stiffness

or rigidity, and this can be used in more senses than one. Kesel

indicates the loins (Psa. 38:7), and by an easy transition it can mean

confidence (Prov. 3:26), but as stiffness and rigidity can be used of

evil as weIl as good, kesel is

often translated "fool" or "folly".

- Machseh. The letter "M" often

indicates that a verb has been turned into a noun, as for example the

Hebrew shaphat "judge" becomes

mishpat "judgment". The verb

from which machseh is formed

is chasah, to take refuge, to

trust (Ruth 2: 12). Machseh is

translated "hope" in Jeremiah 17:17 and Joel 3:16.

- Miqveh. This too is a noun

derived from the verb qavah "to

wait for, expect". Jeremiah uses the word when he speaks of "the hope

of Israel" or "the hope of their fathers" (Jer. 14:8, 50:7). The idea

of confidence or hope seems to lie in the fact that the basic meaning

of qavah, which means to twist

or stretch, came to mean a gathering together (Gen. 1:9) and linen yarn

(1 Kings 10:28), the idea of confidence or trust being developed from

the sense of unity suggested.

- Seber. "Who se hope is in

the Lord" (Psa. 146:5). Little can be said of this word. In Nehemiah

2:13,15 it is translated "view", and so the link between the two meanings

"view" and "hope" seems to be the idea of looking with expectancy, or,

as Hebrews 9:28 puts it, "them that look for Him".

- Tocheleth. "My hope is in

Thee" (Psa. 39:7).

- Yachal. "In Thee, 0 Lord,

do I hope" (Psa. 38:15).

The root idea of these two related words is that of "waiting".

"All the days of my appointed time will I wait" (Job 14:14).

"I will wait for the God of my salvation" (Mic. 7:7).

- Tiqvah. "Thou art my hope,

0 Lord God" (Psa. 71:5). This word belongs to the same group as miqveh

already considered. Its usual translation is "expectation". It is of

interest to note that the first two occurrences of the word use it as

a figure of speech. It is translated "line" in Joshua 2:18 and 21.

"Thou shalt bind this line of scarlet thread in the window."

"She bound the scarlet line in the window."

That line was the concrete evidence and pledge of Rahab's hope, even as in its great antitypical sense it is the pledge of hope for all the redeemed.

- Chul, "to stay". "It is good

that a man should both hope and quietly wait" (Lam. 3:26). This word

is related to yachal, already

examined.

- Yaash. To be desperate, despairing. "There is no hope" (Jer. 2:25). The margin reads "is the case desperate?" This word is not, strictly speaking, one that should be inc1uded under the heading "hope" as it is its very denial.

Although we have listed ten Hebrew words, there are really but seven, as some are derivatives from a common root. To complete this survey of the terms used in the O.T. we give a list of the words, in addition to those already cited, which the LXX translates by elpizo and elpis.

|

Psa. 22:8

|

"He trusted", Hebrew galal, "to roll, to devolve upon". |

|

Isa. 11:10

|

"The Gentiles seek", Hebrew darash,

"to seek, enquire, require". (This passage is quoted in Romans 15:12 where the LXX rendering elpizo is adopted.) |

|

Gen. 4:26

|

"Then began men to call upon the name of the Lord. " The LXX reads, "He hoped to call on the name of the Lord God." This, as the A.V. margin shows, is a highly problematical passage, into which we cannot here enter. |

|

Psa.91:14

|

"Because he hath set his love upon Me." The LXX reads, "For he has hoped in Me." |

|

Jer. 44:14

|

"They have a desire to return", Hebrew nasa,

"to lift up". This, in the LXX in chapter 51:14, "to which they hope in their souls to return". |

|

2 Chrono 13:18

|

"They relied upon the Lord", Hebrew shaan.

LXX reads, "They trusted on the Lord." |

|

Isa. 18:7

|

"A nation meted out", Hebrew

qav. LXX reads, "A nation hoping" because of the use of tiqvah, see above. |

|

Isa. 28:10

|

"Line upon line", Hebrew qav. |

|

Ezek. 36:8

|

"They are at hand to come", Hebrew qarab,

"to be near". LXX reads, "They are hoping to come." |

|

Isa. 28:18

|

''Your agreement with hell shall not stand", Hebrew

chazuth, "vision". LXX reads, "Your trust toward hades shall by no means stand." |

|

2 Chrono 35:26

|

"The acts of Josiah and his goodness", Hebrew chesed,

"kindness". LXX reads, "The acts of Josiah and his hope." |

|

Job 30:15

|

"My soul as the wind", Hebrew nedibah,

"noble one". LXX reads, "My hope is gone like the wind." |

|

Isa. 31:2

|

"Help", Hebrew azar.

LXX, "hope". (Too complicated to set out fully here.) |

|

Isa. 24:16

|

"Glory to the righteous", Hebrew tsebi,

"beauty, desire". LXX reads, "Hope to the godly." |

|

Psa. 60:8

|

"Moab is my washpot", Hebrew sir

rachats. LXX reads, "Moab is the caldron of my hope." |

This has been an exhausting search, and it would be still more so to attempt to unravel all the problems that these translations from the LXX involve. The result of this review, however, enables us to see that "hope" was not only confidence and trust, expectation and desire, but that in the mind of those who wrote Greek the words elpis and elpizo include such terms as "to set one's love", hence Paul's glorious statement in his last epistle concerning those "that love His appearing". To be lifted up as it were on tip-toe of expectancy finds its echo in the eager stretching forth that we read of in Philippians. So also "agreement", "goodness", "soul", "help" and "glory" all enable us to see the fulness of this term. The one passage that baffles us is the last quoted. What was in the mind of the translators when they used the words "Moab is the caldron of my hope" is beyond our own present hope of elucidation. We are sure, however, that this peculiar passage will not spoil the usefulness of the list of terms provided.

Turning now to the N.T., our task is much simpler. Only one Greek word and its compounds are translated "hope", these words are elpizo, to hope, to hope for; proelpizo, to hope before; apelpizo, to hope for again; elpizomenoi, things hoped for; elpis, hope. No other word in the English language can be suggested as a better rendering of elpis than "hope", and yet all have to acknowledge that in common use hope has degenerated in its meaning. We can speak of a forlorn hope, or sometimes a person who has no grounds for hope at all, will say "I hope so". "Expectation is a conviction that excludes doubt" and this is the temper of the word elpis. When we use the word "hope" we must remember to keep it on the ground of confident expectancy, not merely hoping for the "possible" but confidently expecting the fulfilment of a promise. There is no trace of anxiety or fear in the LXX use of elpis or elpizo, although in later classical Greek this element creeps into the word. Cremer's summary is that "Hope is a prospect, gladly and firmly held as a well-grounded expectation of a future good."

Where we read of "hope" in the New Testament we often find in the context a reference either to a "promise" or to a "calling". For example, Paul before Agrippa says:

"And now I stand and am judged for THE HOPE OF THE PROMISE made of God unto our fathers; unto which promise OUR TWELVE TRIBES, instantly serving God day and night, hope to come" (Acts 26:6,7).

Here there is no possibility of making a mistake. Not only is the hope that is in view the fulfilment of a promise, but it is the fulfilment of a specific promise "made of God unto our fathers". Further, there is no ambiguity as to those who entertain this hope; the words "our twelve tribes" are too explicit to permit of spiritualizing. Other examples will occur to the reader, and will come before us in the prosecution of our present study. For the moment it is sufficient that the principle should be clear, that HOPE LOOKS TO THE FULFILMENT OF A PROMISE. It is therefore necessary to discover what promise has been made to any particular company before we can speak with understanding of their hope. Another prerequisite is a knowledge of the "calling" concerned.

"That ye may know what is THE HOPE OF HIS CALLING" (Eph. 1: 18).

"Even as ye are called in ONE HOPE OF YOUR CALLING" (Eph. 4:4).

The realization of our hope in the future will be in agreement with our calling now by faith.

"Now faith is the substance of things HOPED for" (Heb. 11 :1).

Recent discoveries among the papyri of Egypt have brought to light the fact that the word "substance" was used in New Testament times to signify the "Title Deeds" of a property. Every believer holds the title-deeds now, by faith, the earnest and first-fruits of the inheritance that will be entered when his hope is realized. As every believer does not necessarily belong to the same calling, and most believers grant a distinction between Kingdom and Church, while some realize the further distinction between Bride and Body, it follows that the character of the calling must be settled before the hope can be defined.

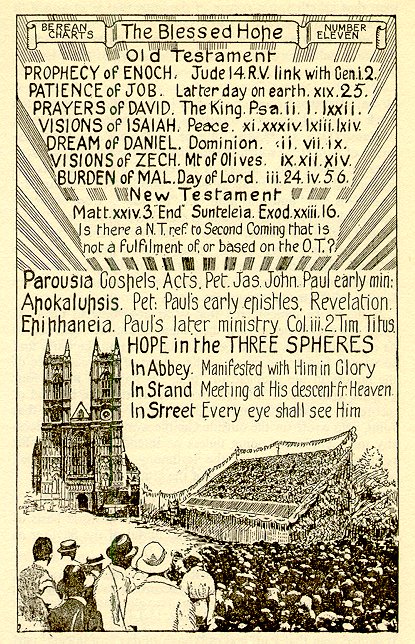

Three spheres

of blessing

There are at least three distinct spheres of blessing indicated in the New Testament:

- The Earth. - "Blessed are

the meek; for they shall inherit the earth" (Matt. 5:5).

- The Heavenly City. - "The

city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem . . . and church of the

firstborn, which are written in heaven" (Heb. 12:22,23).

- Far above all. - "He ascended up, far above all heavens" (Eph.4:10). "And made us sit together in heavenly places" (Eph. 2:6).

These three spheres of blessing correspond to three distinct callings:

- The Kingdom. - "Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done in earth" (Matt. 6:10).

- The Bride. - "The Bride, the Lamb's wife . . . the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God" (Rev. 21:9,10).

- The Body. - "His body. . . the church: whereof I (Paul) am made a minister, according to the dispensation of God which is given to me for you . . . the mystery which hath been hid from ages and from generations" (Col. 1 :24-26).

These three spheres of blessing, each with its special calling, have associated with them three groups of people in the N.T. The first sphere of blessing is exclusive to ISRAEL according to the flesh; the second to believers from among both "JEW and GREEK", while in the third sphere the calling is addressed to "YOU GENTILES".

- Israel according to the flesh.

- "My kinsmen according to the flesh, who are Israelites; to whom pertaineth

the adoption, and the glory, and the covenants, and the giving of the

law, and the service of God, and the promises, whose are the fathers,

and of whom as concerning the flesh Christ came, Who is over all, God

blessed for ever. Amen" (Rom. 9:3-5).

- Abraham's seed (includes believing Gentiles). - "Having begun in the Spirit, are ye now made perfect by the flesh? . . . they which are of faith, the same are the children of Abraham. . . . For as many of you as have been baptized into Christ, have put on Christ. There is neither Jew or Greek . . . for ye are .all one in Christ Jesus. And if ye be Christ's, then are ye Abraham's seed, and heirs according to the promise" (Gal. 3:3,7,9,27-29).

If, at the end of verse 28, we "shut the book", we may "prove" that the blessed unity indicated by the words "neither Jew nor Greek" refers to the "Church which is His Body". If, however, we keep the book open, we see that such is not the sequel, but that this new company are "Abraham's seed", and the hope before them "the promise" made to Abraham. The reader may readily assent to this, but we would urge him to remember that I Thessalonians and Galatians were both written before Acts twenty-eight, and therefore before the revelation of the Mystery. The hope then of 1 Thessalonians four belongs to the same calling as that of Galatians and cannot constitute the hope of the Mystery.

- The One New Man. - "Where

there is neither Greek nor Jew . . . but Christ is all and in all" (Col.

3:11).

"That He might create in Himself of the twain one new man, so making peace" (Eph. 2:15 R.V.).

"That the Gentiles should be fellow-heirs" (Eph. 3:6).

The limits of this article will not permit of extensive proofs of the suggestions made in the foregoing paragraphs, or of a detailed exposition of the passages concerned; but we believe that the matter is sufficiently clear for us to go forward with our inquiry. Seeing then that there are three spheres of blessing, with their three associated callings, we should expect to find three phases of the Coming of the Lord. These three phases are presented in the following Scriptures: .

- Kingdom on earth. - HOPE. Matt.24-25.

- Abraham's seed (heavenly calling). - HOPE. 1 Thess. 4.

- Far above all. - HOPE. Col. 3:4.

Let us look at each phase of the second advent as presented by these three passages.

THE HOPE OF THE FIRST SPHERE

The

Sign of the coming of the Son of Man

The earthly ministry of the Lord Jesus Christ was limited to the people of Israel, and had special regard to the promise made to David concerning Israel's King. It also had in view the promise made to Abraham concerning the blessing of all the families of the earth, but did not, at that time, extend to them, being concentrated rather upon Israel from whom, as the appointed channel, the blessing should flow to all nations. We shall now bring Scriptural proof of these statements, and then proceed to show that Matthew twenty-four and twenty-five speak of the hope of ISRAEL, and that this phase of the second advent has nothing to do with the hope of the "church".

- Proof that the earthly ministry was

limited in the first instance to Israel.

"Now I say that Jesus Christ was a minister of the CIRCUMCISION for the truth of God, to confirm the promises made unto the FATHERS" (Rom. 15:8).

"Go not into the way of the Gentiles, and into any city of the Samaritans enter ye not; but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of ISRAEL" (Matt. 10:5-6).

"I am not sent but unto the lost sheep of the house of ISRAEL" (Matt. 15:24).

- Proof that the promise made to David

concerning a King was in view.

"Where is He that is born KING of the Jews? . . . in Beth1ehem" (Matt. 2:2-5).

"Tell ye the daughter of Sion, Behold, thy KING cometh unto thee" (Matt. 21 :5).

"What think ye of Christ, whose Son is He? They say unto Him, The Son of DAVID" (Matt. 22:42).

"David. . . being a prophet, and knowing that God had sworn with an oath to him, that of the fruit of his loins, according to the flesh, HE WOULD RAISE UP CHRIST TO SIT ON HIS THRONE; He seeing this before, spake of the resurrection of Christ" (Acts 2:30,31).

- Proof that the promise to Abraham

concerning Israel as the chosen channel of blessing to the Gentiles

was in view.

"Ye are the children of the prophets, and of the covenant which God made with our fathers, saying unto Abraham, And in thy seed shall all the kindreds of the earth be blessed. UNTO YOU FIRST God, having raised up His Son Jesus, sent Him to bless YOU, in turning away every one of you from his iniquities" (Acts 3:25,26).

The consideration of these Scriptures in their setting provides sufficient proof for the statements made concerning the character of the Saviour's earthly ministry.

We are now in a position to consider Matthew twenty-four and twenty-five, which is a prophecy of the second coming of Christ, and concerns the hope of Israel as distinct from the hope of the church.

The threefold prophecy of the coming of the Lord as revealed in Matthew twenty-four was given in answer to the threefold question of the disciples-

"When shall these things be?"

"What shall be the sign of Thy coming?"

"And the end of the world (age)?"

The evidence which follows, sufficiently shows that in this passage the hope of Israel and not the hope of "the church which is His Body" is the subject.

Three proofs that Matthew twenty-four

speaks of the Hope of Israel

First the word translated "end" is sunteleia, a word at that time well known to every Jew, for it was the name of the third great feast, namely "the feast of ingathering, which is in the end of the year" (Exod. 23:16). This is evidence that Israel's hope is in view.

Secondly, we find that this coming of the Lord is to be preceded by "wars and rumours of wars". Because of the fact that there have been, and yet will be, many wars and rumours of wars since the setting aside of Israel, these words, as they stand, cannot be construed as evidence that Israel's hope is in view. If however we turn to the O.T. origin of the reference: "For nation shall rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom" (Matt. 24:7), we shall see that it comes from Isaiah's prophetic "Burden of Egypt" (Isa. 19:1,2), the passage ending with the words "Blessed be Egypt My people, and Assyria the work of My hands, and Israel Mine inheritance" (Isa. 19:25). This reference, therefore, when seen in the light of its O.T. setting, gives further evidence for the fact that Israel is in view in Matthew twenty-four.

Thirdly, this coming of the Lord takes place after the prophetic statements of Daniel 9:27 and 12:11 have been fulfilled.

"When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, stand in the holy place . . . then shall be great tribulation . . . IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE TRIBULATION of those days . . . shall appear the sign of the Son of man in heaven . . . and they shall see the Son of man COMING IN THE CLOUDS OF HEAVEN" (Matt. 24:15-30).

As the detailed exposition of this chapter is not our purpose, and as these three items provide proof beyond dispute that the second coming of Christ as here made known cannot be the hope of the church, we feel that no unbiased reader will desire further delay in prosecuting our inquiry.

THE HOPE OF THE SECOND SPHERE

The Acts and Epistles of the Period

We must now turn our attention to the evidence of Scripture as to the character of the Hope during the period covered by the Acts of the Apostles. Some commentators on this book appear to forget that it is the record of the "Acts" of the Apostles, and had no existence until those "Acts" were accomplished. If the founding of the church at Corinth chronicled in Acts eighteen be an act of the apostle Paul, both Crispus (verse 8) and Sosthenes (verse 17) being mentioned by name, then the epistle written by the same apostle to the same church, again mentioning Crispus and Sosthenes by name, must be included as the Divine complement of the record of Acts eighteen. The aspect of the Hope in view in the Acts and in the epistles written during that period to the churches founded by the Apostles must of necessity be the same. Any attempt to make the ministry of Paul during the Acts differ from the epistles of the same period is false, and must be rejected. There can be no doubt that the hope entertained by the churches during the period covered by the Acts of the Apostles was a phase of the Hope of Israel. This will, we trust, be made clear to the reader by the quotations and comments given hereafter.

- "When they therefore were come together, they asked of Him, saying, Lord, wilt Thou at this time restore again the kingdom to Israel?" (Acts 1:6).

This question arose after the forty days' instruction given by the risen Christ to His disciples, during which time He not only opened the Scriptures, but "their understanding" also (Luke 24:45).

- "Repent . . . and He shall send Jesus Christ, Which before was preached unto you: Whom the heaven must receive until the times of restitution of all things, which God hath spoken by the mouth of all His holy prophets since the world began. . . . Ye are the children of the prophets. . . . Unto you first. . ." (Acts 3:19-26).

These words of Peter, spoken after Pentecost, cannot be separated from the hope of Israel without violence to the inspired words. It may be, that some readers will interpose the thought: "These are from the testimony of Peter; what we want is the testimony of Paul." We therefore give two more extracts from the Acts, quoting this time from the ministry of Paul.

- "And now I stand and am judged for the hope

of the promise made of God unto our fathers: unto which promise our

twelve tribes, instantly serving God day and night, hope to come" (Acts

26:6,7).

- "Paul called the chief of the Jews together . . . because that for the hope of Israel I am bound with this chain" (Acts 28:17,20).

Not until the Jewish people were set aside in Acts 28:25-29 does Paul become "the prisoner of Jesus Christ for you Gentiles". Until it was a settled fact that Israel would not repent and that the promise of Acts 3:19-26 would be postponed, the hope of Israel persisted, and all the churches that had been brought into being up to that time were of necessity associated with that h9pe. See the testimony of Romans, which is set out in much fuller detail after the reference to the heavenly calling is completed.

The Heavenly Calling

We have already drawn attention to the intimate association that exists between "hope", "promise" and "calling". We must pause for a moment here to remind the reader that Abraham stands at the head of two companies: an earthly people, the great nation of Israel; and a heavenly people, associated with the heavenly phase of God's promise to Abraham, and made up of the believing remnant of Israel and believing Gentiles. This heavenly side of the Abrahamic promise is referred to by the Apostle in Hebrews and Galatians:

"He looked for a city. . . . They seek a country. . . . They desire a better country, that is, an heavenly; wherefore God is not ashamed to be called their God: for He hath prepared for them a city" (Heb. 11:10,14,16).

"If ye be Christ's, then are ye Abraham's seed, and heirs according to the promise. . . . Jerusalem which is above is free, which is the mother' of us all" (Gal. 3:29, 4:26).

This heavenly calling of the Abrahamic promise constitutes the Bride of the Lamb, as distinct from the restored Wife, which refers to Israel as a nation. We leave the reader to verify these statements for himself by referring to Isaiah, Jeremiah and Hosea, where Israel's restoration is spoken of under the figure of the restored Wife; and to the Book of the Revelation where the heavenly city is described as the Bride. During the time of the Acts of the Apostles, the churches founded by Paul were "Abraham's seed, and heirs according to the promise" (Gal. 3:29). The Apostle speaks of "espousing them to one husband, that I may present you as a chaste virgin to Christ" (2 Cor. 11:2).

This heavenly phase of the hope of Israel was the hope of all the churches established during the Acts, until Israel was set aside as recorded in Acts twenty-eight.

The Testimony of Romans

The epistles written by Paul before his imprisonment were Galatians, Hebrews, Romans, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, and 1 and 2 Corinthians. We are sure that any well-instructed reader who was asked to choose from this set of epistles the one giving the most recent as well as the most fundamental teaching of the apostle for this period, would unhesitatingly choose the epistle to the Romans. In this epistle we have the solid rock foundation of justification by faith, where "no difference" can be tolerated between Jew and Gentile. When, however, we leave the sphere of doctrine (Rom. 1-8), and enter the sphere of dispensational privileges, we discover that differences between Jewish and Gentile believers remain. The Gentile, who was justified by faith, was nevertheless reminded that he was at that time in the position of a wild olive, graft into the true olive tree, from which some of the branches had been broken off through unbelief. The grafting of the Gentile into Israel's olive tree was intended (speaking after the manner of men) to provoke Israel to jealousy. When, in the days to come, these broken branches shall be restored, "All Israel shall be saved".

These statements from Romans eleven are sufficient to prevent us from assuming that, because there is evidently DOCTRINAL equality in the Acts period, there is also DISPENSATIONAL equality. This is not so, for Romans dec1ares that the Jew is still "first", and the middle wall still stands, making membership of the One Body as revealed in Ephesians impossible.

In Romans fifteen we have a definite statement concerning the hope entertained by the church at Rome. Before quoting the passage, Romans 15:12 and 13, we would advise the reader that the word "trust" in verse 12 is elpizo, and the word "hope" in verse 13 elpis. There is also the emphatic article "the" before the word "hope" in verse 12. Bearing these points in mind we can now examine the hope entertained by the church at Rome, as ministered to by Paul before his imprisonment.

"There shall be a Root of Jesse, and He that shall rise to reign over the Gentiles; in Him shall the Gentiles hope. Now the God of that hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, that ye may abound in hope, through the power of the Holy Ghost" (Rom. 15:12,13).

Here we are on firm ground. Paul himself teaches the church to look for the millennial kingdom and for the Saviour as the "Root of Jesse" Who shall "reign over the Gentiles". How can this hope be severed from "the hope of Israel"? How can it be associated with the "Mystery" which knows nothing of Abraham, or of Israel, but goes back before the "foundation of the world", and reaches up to heavenly places? In case the reader should be uncertain of Paul's references to the millennial Kingdom, we quote from Isaiah eleven:

"And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse. . . . He shall smite the earth with the rod of His mouth, and with the breath of His lips shall He slay the wicked. . . . The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb. . . . And in that day there shall be a Root of Jesse, which shall stand for an ensign of the people; to It shall the Gentiles seek: and His rest shall be glorious" (Isa. 11:1,4,6,10).

The reader should consult the note on Isaiah 11:4 given in The Companion Bible, where the reading, "He shall smite the oppressor" (ariz) is preferred to the A.V. "He shall smite the earth" (erez). This reading establishes a link with 2 Thessalonians 2:8:

"And then shall that Wicked be revealed, whom the Lord shall consume with the spirit of His mouth, and shall destroy with the brightness of His coming."

Before referring to 1 Thessalonians four, which presents the hope of the church at that time very c1early, we must say something about the strange avoidance of the second epistle that so many manifest when dealing with this subject.

The Importance of a Second Epistle

If a business man were to treat his correspondence in the way that some believers treat the epistles of Paul, the results would be disastrous. A second letter, purporting to rectify a misunderstanding arising out of a previous letter, would, if anything, be more important and more decisive than the first; yet there are those whose system of interpretation demands that they shall claim 1 Thessalonians four as the revelation of their hope, who nevertheless either neglect the testimony of 2 Thessalonians or explain it away as of some future mystical company unknown to the Apostle. Let us first verify that these two epistles form a definite pair, written by the same writer, at the same period, to the same people, about the same subject.

|

Identity of Address

|

|

| FIRST EPISTLE | "Paul, and Silvanus, and Timotheus, unto the church of the Thessalonians which is in God the Father and in the Lord Jesus Christ" (1 Thess. 1:1). |

| SECOND EPISTLE | "Paul, and Silvanus, and Timotheus, unto the church of the Thessalonians in God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ" (2 Thess. 1:1). |

|

Identity of Theme |

|

| FIRST EPISTLE | "Remembering without ceasing your work of faith, and labour of love, and patience of hope in our Lord Jesus Christ, in the sight of God and our Father" (1 Thess. 1:3). |

| SECOND EPISTLE | "We are bound to thank God always for you, brethren, as it is meet; because that your faith groweth exceedingly, and the love of every one of you all towards each other aboundeth; so that we . . . glory . . . in your patience" (2 Thess. 1:3). |

| FIRST EPISTLE | "The coming of our Lord Jesus Christ with all His saints" (1 Thess. 3:13). (A reference to Deut. 33:2, Psa. 68:17 and Zech. 14:5 will show that the "saints" here are the "holy angels" and not the church). |

| SECOND EPISTLE | "The Lord Jesus shall be revealed from heaven with His mighty angels, in flaming fire" (2 Thess. 1:7,8). |

The Special Purpose of Second Thessalonians

The Thessalonian Church had been disturbed by the circulation of a letter purporting to have come from the Apostle, and by certain messages given by those who claimed to have "the spirit". These messages distorted the Apostle's teaching concerning the coming of the Lord, as taught in the church while he was with them and mentioned in the fourth chapter of his letter.

"We beseech you, brethren . . . that ye be not soon shaken in mind or be troubled, neither by spirit, nor by word, nor by letter as from us, as that the day of Christ (or the Lord) is at hand. Let no man deceive you by any means: for that day shall not come, except there come a falling away first" (2 Thess. 2:1-3).

Before the hope of the church at Thessalonica could be realized, certain important prophecies awaited fulfilment. As we have seen, the hope during the period of the Acts (and therefore that of 1 Thessalonians four) was essentially the hope of Israel. When 1 Thessalonians four was written, Israel were still God's people. The Temple still stood, and the possibility (speaking humanly) of Israel's repentance had still to be reckoned with. If the hope of Israel was about to be fulfilled, then Daniel 9-12 must be fu1fi1led also, together with many other prophecies of the time of the end. This we have seen to have been the testimony of the Lord Himself in Matthew twenty-four, and .so far Israel had not been set aside (i.e. when the epistles to the Thessalonians were written).

The following predicted events must precede the coming of the Lord as revealed in 1 and 2 Thessalonians:

- The apostasy must come first ("falling away", Greek apostasia).

- The Man of Sin must be revealed in the Temple (the word "Temple" is the same as in Matthew 23:16).

- The coming of this Wicked One will be preceded by a Satanic travesty of Pentecostal gifts. (The same words are used as of Pentecost, with the addition of the word "lying".)

- This Wicked One shall be "consumed" and "destroyed" with the brightness of the Lord's coming (see Isaiah 11:4, revised reading).

All this the Apostle had told the Thessalonian church when he was with them, before he wrote 1 Thessalonians four (see 2 Thess. 2:5).

The Thessalonians had already been taught by the Apostle himself concerning the events of prophecy, and would doubtless have read 1 Thessalonians four in harmony with his teaching had they not been deceived by fa1se interpretations. The reference to the Archangel would have taken them back to Daniel 10-12. The epistle of Jude uses exactly the same word as is used here, and tells us that the Archange1's name is Michae1 (Jude 9). Immediately following the great prophecy of the seventy weeks, with its climax in the "Abomination of desolation", we have the revelation of Daniel ten. There the veil is partially withdrawn, and a glimpse is given of the Satanic forces behind the "powers that be". Michae1 is said to be "your Prince" and in Daniel twelve we read:

"And at that time shall Miehael stand up, the great prince which standeth for the children of thy people: and there shall be a time of trouble, such as never was since there was a nation . . . and many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake" (Dan. 12:1,2).

Here we have Michael identified with the people of Israel, and when he stands up the great tribulation and the resurrection take place. This FOLLOWS THE EVENTS OF DANIEL ELEVEN, which are briefly summarized in 2 Thessalonians two. Compare, for example, the following passages:

"He shall exalt himse1f, and magnify himself above every god, and shall speak marvellous things against the God of gods" (Dan. 11:36).

"Who opposeth and exalteth himself above all that is called God, or that is worshipped" (2 Thess. 2:4).

1 and 2 Thessalonians and Revelation thirteen

If the reader would read consecutively Daniel nine, ten, e1even and twelve, 1 Thessalonians four and five, 2 Thessalonians one and two, and Revelation thirteen, the testimony of the truth itself would be so strong as to need no human advocate. Our space is limited, and we therefore earnestly ask all who value the teaching of the Scriptures regarding "that blessed hope" to read and compare these portions most carefully and prayerfully. When this is done, let the question be answered: "what have all these Scriptures to do with the church of the dispensation of the Mystery, a church called into being consequent upon Israe1's removal and the suspension of Israel's hope?" The answer can only be that, while the close association of the hope of the Thessalonians with the hope of Israel was consistent with the character of the dispensation then in force, the attempt to link the "one hope of our calling" with prophetic times is a dispensational anachronism and a failure to distinguish things that differ.

"Till He Come"

The coming of the Lord referred to in 1 Corinthians 11 :26 must be the same hope as was entertained by the Thessalonians, and by the church at Rome (Rom. 15:12,13, see p. 143). The Apostle himself summarizes this hope in Acts 28 :20 as the "hope of Israel". The Corinthian epistle deals with a variety of subjects, and is addressed to different sections of the church. Some called themselves by the name of Paul, others by the name of Cephas. Some were troubled with regard to the question of marriage, and others with regard to moral questions. The section in which the words "till He come" occur is addressed to those whose "fathers" were "baptized unto Moses" (1 Cor. 10:1); whereas the section that immediately follows is addressed to Gentiles (1 Cor. 12:2). Concerning the question of marriage, the Apostle writes:

"I suppose therefore that this is good for the present distress. . . . The time is short: it remaineth, that both they that have wives be as though they had none; and they that weep, as though they wept not. . . and they that buy, as though they possessed not" (1 Cor. 7:26-30).

Shall we fall into the error of teaching, as some have taught, that marriage is wrong because of what Paul says in this chapter? If we do, what shall we say of his wonderful words concerning husband and wife in Ephesians five? Or of his advice that the younger women should not only marry, but marry again if left as widows? (1 Tim. 5:9-14). The right interpretation is clearly that Paul's advice in 1 Corinthians seven was true AT THE TIME, because the Second Coming of Christ was expected to take place during the lifetime of some of his hearers. He speaks as he does, "because of the present necessity", and because "the time is short". When writing to the Thessalonians, he rightly identifies himself with the imminent hope of the Lord's coming by saying: "We which are alive" (1 Thess. 4).

The "present necessity" of 1 Corinthians seven is no longer applicable on account of the failure of Israel and the suspension of their hope. So in 1 Corinthians eleven, the teaching of the chapter was only true while the hope of that calling was still imminent. When the people of Israel passed into their present condition of blindness, as they did in Acts twenty-eight, their hope passed with them, not to be revived until the end of the days, when the Apocalypse is fulfilled. Meanwhile a new dispensation has come in, a dispensation associated with a "mystery" and unconnected with Israel. In the very nature of things a change of dispensation means a change of calling. It introduces a new sphere and a fresh set of promises, and demands a re-statement of its own peculiar hope.

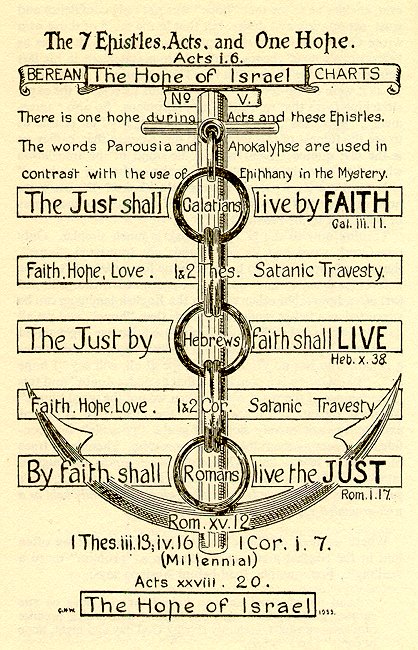

The reader is referred to the chart on p. 134, where the inter-relation of the epistles, the Acts and the hope is set forth in diagrammatic form. The references should be verified and nothing taken for granted, so that we may approach the third section of our theme with preparedness of mind.

HOPE OF THE THIRD SPHERE

The Manifestation in Glory

Before considering the special characteristics of the hope of the church of the One Body, it may be of service to set out some of the distinctive features of the dispensation of the Mystery, so that, perceiving the unique character of its calling, we shall be compelled to believe the unique character of its hope.

Special features of the present dispensation

First of all let us observe two features that marked the previous dispensation, but are now absent.

- The presence and prominence of Israel.

The testimony of the Gospels (Matt. 10:6, 15:24), the witness of Peter (Acts 3:25,26), and the testimony of Paul (Rom. 1:16, 3:29, 9:1-5, 11:24-25 and 15:8), all combine to show that the nation of Israel was an important factor in the outworking of the purpose of the ages, and that during the period covered by the Gospels and the Acts, no blessing could be enjoyed by a Gentile in independence of Israel. It is evident that with the setting aside of this favoured people, a change in dispensation was necessitated.

- The presence and prominence of miraculous

gifts.

Throughout the public ministry of the Lord Jesus, and from Pentecost in Acts two until the shipwreck on the island of Melita in Acts twenty-eight, supernatural signs, wonders and mirac1es accompanied and confirmed the preached word. Not only did the Lord Himself and also His apostles work mirac1es, but during the time of the Acts ordinary members of the church were in possession of spiritual gifts in such abundance that they had to seek the Apostle's advice as to their regulation in the assembly (1 Cor. 14:26-40). The mirac1es of Mark sixteen, Acts two and 1 Corinthians twelve to fourteen are not the normal experience of the church of today. Their absence, together with the setting aside of the people of Israel, constitute two pieces of negative evidence in favour of a new dispensation. We are not, however, limited to negative evidence. Scripture also provides definite evidence of a positive kind, which we must now consider.

- The prison ministry of the Apostle

Paul.

When Paul spoke to the elders of the church at Ephesus, he made it quite plain that one ministry was coming to an end and another, closely associated with prison, was about to begin. Re reviewed his past services among them, and told them among other things that they should see his face no more (Acts 20:17-38). Later, before King Agrippa, he reveals the important fact that when he was converted and commissioned by the Lord, in Acts nine, he had been told that at some subsequent time the Lord would appear to him again and give him a second commission (Acts 26:15-18).

- The dispensational boundary of Acts

twenty-eight.

Right up to the last chapter of the Acts, Israel and miraculous gifts continued to occupy their pre-eminent place (Acts 28:1-10, 17,20). Upon arrival at Rome, Paul, although desirous of visiting the church (Rom. 1:11-13), sent first for the "chief of the Jews", telling them that "for the hope of Israel" he was bound with a chain. After spending a whole day with these men of Israel, seeking unsuccessfully to persuade them "concerning Jesus" out of the law and the prophets, he pronounces finally their present doom of blindness, adding:

"Be it known therefore unto you, that the salvation of God is

sent unto the Gentiles, and that they will hear it" (Acts 28:28).

During the two years of imprisonment that followed, the Apostle ministered to all that came to him, teaching those things which "concern the Lord Jesus Christ" with no reference this time either to the law or to the prophets (Acts 28:30,31).

- The present dispensation a new revelation.

The omission of "the law and the prophets" from Acts 28:31, as compared with verse 23, is an important point. Throughout the early ministry of the Apostle he makes continual and repeated appeal to the O.T. Scriptures. But when one examines the "Prison Epistles" one is struck by the absence of quotation. The reason for this change is that Paul, as the prisoner of Jesus Christ for the Gentiles, received the Mystery "by revelation" (Eph. 3:1-3). This mystery had been hidden from ages and generations, until the time came for Paul to be made its minister (Col. 1:24-27). It could not, therefore, be found in the O.T. Scriptures.

- Some special features of this new

calling.

- This church was chosen "before the foundation of the world" (Eph. 1 :4) and "before age-times" (2 Tim. 1 :9).

- This church finds its sphere of blessing "in heavenly p1aces, far above all principality and power. . . seated together in heavenly places in Christ Jesus" (Eph. 1:3,20,21,2:6).

- This church is not an "evolution", but a new "creation", the peculiar advantage of being a Jew, even though a member of the church, having disappeared with the middle wall of partition (Eph. 2:14-19).

- This church is the One Body of which Christ is the Head, and in which all members are equal (Eph. 1:22,23, 3:6), a relationship never before known.

- The Prison Epistles.

While the very nature of things demands a new dispensation consequent upon Israel's removal, we are not left to mere inference. There is a definite section of the N.T. with special teaching relating to the church of the present dispensation. This 1s found in the epistles written by Paul as the prisoner of the Lord for us Gentiles. These epistles are five in number, but we generally refer to the "four Prison Epistles" , as that to Philemon is practica1 and personal and makes no contribution to the new teaching.

The four Prison Epistles are:

A EPHESIANS. The Dispensation of the Mystery. Basic Truth

B PHILIPPIANS. The Prize. Outworking.

A COLOSSIANS. The Dispensation of the Mystery. Basic Truth

B 2 TIMOTHY. The Crown. Outworking.

The reader will find in each of these epistles, evidence that they were written from prison and that they form part of the ministry referred to in Acts 28:31.

The above notes on features (1) to (7) are necessarily brief and are not intended to do anything more than provide the merest outline of the subject. Any reader who is not convinced as to the peculiar and unique character of these prison epistles and the dispensation they reveal, should give them a personal study, noting all their claims, and their distinctive features. This article has not been written to prove to the satisfaction of all that a new dispensation commenced at Acts twenty-eight, but has been prepared rather as a help to those who, having realized that a change most certainly did take place in the dispensational dealings of God with men at that time, de sire to understand what effect this change had upon the hope of the church.

The new phase of Hope necessitates Prayer

While prayer should accompany the Word at all times, there is no need to pray for "revelation" concerning one's hope if it be already revealed. Words can scarcely be clearer than those employed in 1 Thessalonians four, and if this chapter still represented the hope of the church of the One Body, there would be no need for the Apostle to speak as he does in Ephesians one. In verse 17, he prays that the saints might receive "the spirit of wisdom and revelation in the knowledge of Him . . . that ye may know what is the hope of His calling" (Eph. 1:17,18).

It might be well if the reader pondered the marginal reading of Ephesians 1:17 where, instead of "in the knowledge of Him", we read, "for the acknowledging of Him". This raises a most important point. Many fail to go forward with the truth, not because of inability to understand the meaning of plain terms, but because of failure to "acknowledge Him". The Apostle pauses in his teaching to tell his hearers that before another step can be taken, acknowledgment of what has already been revealed must be made. To acknowledge the truth of the Mystery is to put oneself out of favour with denominationalism; and many a child of God who says, "I do not see it", is really making a confession of failure to acknowledge the revelation of truth connected with the ascended Lord.

This new phase of Hope is associated with a

Promise

We have already seen that hope and promise are necessarily linked together. We discovered that the promises that were the . basis of expectation during the Acts were the promises "made unto the fathers". Now the fathers had no promises made to them concerning heavenly places "where Christ sitteth at the right hand of God". They knew nothing of a church where Gentile believers would be on perfect equality with Jewish believers. The promises made to the fathers never extended beyond "the Bride" or "the Heavenly Jerusalem", but in Ephesians we have "the Body" and a sphere "far above all".

In Ephesians 1:12, where the A.V. reads "first trusted", the margin reads "hoped"; and as we cannot speak of "the blessed trust" or "the trust of the second coming" it is best to keep to the translation "hope". The actual word used is proelpizo, to "fore-hope". Of this prior hope the Holy Spirit is the seal, and as such is "the Holy Spirit of promise".

What promise is in view? There is but one promise in the Prison Epistles. The Gentiles who formed the church of the One Body were by nature

"aliens from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers from the covenants of promise" (Eph. 2:12),

but through grace they became

"fellow-heirs, and of the same body, and partakers of His promise in Christ by the gospel; whereof I (Paul) was made a minister" (Eph. 3:6-7).

This promise takes us back to the period of Ephesians 1:4, "before the foundation of the world":

"According to the promise of life, which is in Christ Jesus . . . according to His own purpose and grace, which was given us in Christ Jesus, before the world began" (before age-times) (2 Tim. 1:1,9).

It is this one unique promise that will be realized when the blessed hope before the church of the One Body is fulfilled. Its realization is described by the Apostle in Colossians three:

"When Christ, Who is our life, shall appear, then shall ye also appear with Rim in glory" (Col. 3:4).

It is impossible to defer this "appearing" until after the Millennium, for the church is waiting for "Christ their fife" and so awaiting "the promise of life", which is their hope. The word "appearing" might be translated "manifestation" , and will be familiar to most readers in the term "epiphany".

Parousia and Epiphany

Believing as we do that all Scripture is given by inspiration of God, we must be careful to distinguish between the different words used by God when speaking of the hope of His people. We observe that the word parousia usually translated "coming" , is found in such passages as the following:

- "What shall be the sign of Thy COMING and of the end of the age?" (Matt. 24:3).

- "The COMING of the Lord" (1 Thess. 4:15).

- "The COMING of our Lord Jesus Christ" (2 Thess. 2:1).

- "They that are Christ's at His COMING" (1 Cor. 15:23).

- "The COMING of the Lord draweth nigh" (Jas. 5:8).

- "The promise of His COMING" (2 Pet. 3:4).

- "Not ashamed before Him at His COMING" (1 John 2:28).

This word is used to describe the hope of the church during the period when "the hope of Israel" was still in view. Consequently we find it used in the Gospel of Matthew, by Peter, James and John, ministers of the circumcision, and by Paul in those epistles written before the dispensational change of Acts twenty-eight.

A different word is used in the Prison Epistles. There, the word parousia is never used of the Lord's coming or of the hope of the church, but the word epiphany. In 1 Thessalonians four the Lord descends from heaven; in 2 Thessalonians one He is to be revealed from heaven. This is very different from being manifested "in glory", i.e. where Christ now sits "on the right hand of God". While, therefore, the hope before all other companies of the redeemed is "the Lord's coming", the "prior-hope" of the church of the Mystery is rather "their going" to be "manifested with Him in glory".

While the epistle to Titus is not a "Prison Epistle", it belongs to the same group as 1 and 2 Timothy. There, too, we read that we should live

"looking for that blessed hope, and the manifestation of the glory of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ" (Titus 2:13).

The Marriage of the King's Son

We may perhaps illustrate these different aspects of the Second Advent by using the occasion of the marriage of the King's son at Westminster Abbey. The marriage is one, whether witnessed in the Abbey itself, from a grandstand, or from the public footway. So, whatever our calling, the hope is one in this respect, that it is Christ Himself. Nevertheless, we cannot conceive of anyone denying that to be permitted to be present in the Abbey itself is something different from sitting in a grandstand until the King's son, accompanied by "shout" and "trumpet", descends from the Abbey to be met by the waiting people. These waiting people outside the Abbey form one great company, although differentiated as to point of view. So the early church, together with the Kingdom saints, form one great company, although some, like Abraham, belong to "the heavenly calling" connected with Jerusalem that is above, while others belong to the Kingdom which is to be "on earth". We can hardly believe that any subject of the King would "prefer" the grandstand or the kerb to the closer association of the Abbey itself; and we can hardly believe that any redeemed child of God would "prefer" to wait on earth for the descent of the Lord from heaven if the "manifestation with Him in glory" were a possible hope before him. We cannot, however, force these things upon the heart and conscience. We can only respond to the exhortation to be "ready always to give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that is in you with meekness and reverence" (1 Pet. 3:15).

Further information and fuller argument on special aspects will be found in the articles entitled THE LORD's SUPPER, ISRAEL, THREE SPHERES and ACTS.

Home | About LW | Site Map | LW Publications | Search

Developed by ©

Levend Water All rights reserved