DISPENSATIONAL TRUTH

By Charles H. Welch

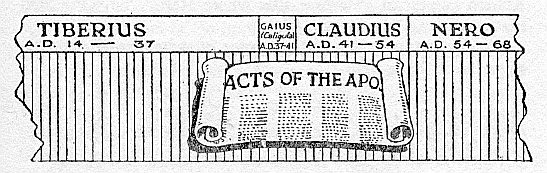

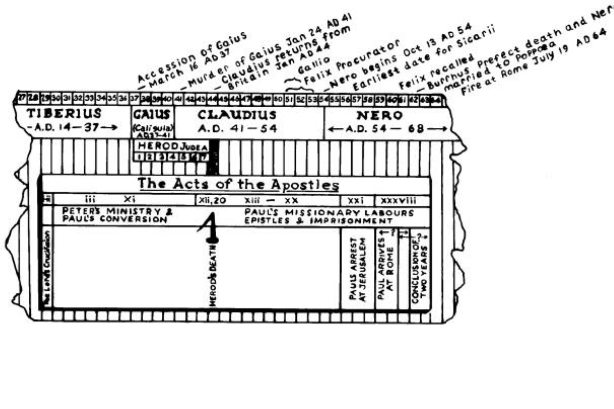

It should be stated at the outset that the chronology of the Acts must ever remain somewhat tentative, owing to the nature of the data provided. The chronology of the book of Genesis can be built up from Adam, all authorities agreeing on the date of Joseph’s death recorded in Genesis 50:26, 1635 B.C. The chief purpose of chronology in the Bible is to establish an unbroken chain of events that link Adam to Christ. That being accomplished, chronology has served its purpose, and the dates that do come in the New Testament are isolated, and not links in a chain. However, that is no reason why we should not use what information we have, in order that the great historic book of the New Testament namely the Acts should be seen in its relationship both with the outside world and the unfolding of the Divine purpose. Let us approach the question in its broadest outline first. The reign of four Roman Emperors covers the period of the Acts.

Just how far the scroll will extend when spread out is now the object of our inquiry.

While these four Emperors and their reigns more than cover the period of the Acts, we have no definite point of contact recorded either in sacred or secular history where, in A.D .... Paul, or Peter, did so-and-so. We must seek some definite point of time where the scroll of the Acts can be pinned down to the calendar of the world. If the wider range of Roman Emperors fails us here, a narrower and lesser dynasty supplies this need. There is one incident recorded in the Acts, the date of which is known; that is the tragic death of Herod (Acts 12:20-23).

The history of Herod Agrippa I is a chequered one. Josephus records (Ant. xix: 8, 2) that Herod died in ‘the 7th year of his reign and the 54th year of his life’. Again he tells us (Bell. Jud. ii, xi: 6) that Agrippa died soon after the completion of his third year as King over all Judea. Now let us see whether we can arrive at the date by these two items.

- When did Herod begin his reign?

Secular history supplies the answer: ‘Not many days’ after the accession of Gaius. When was that? ‘March 16th, A.D. 37’. lf we add 37 A.D. and 7 together, we have the date of Herod’s death as A.D. 44.

- When did Herod begin to reign over ALL JUDEA?

Gaius was murdered on January 24th, A.D. 41 and on the accession of Claudius (Ant. xix: 8,2), Herod was made King of Jud -a and Samaria. Add to A.D. 41 the 3 years of Herod’s reign, and again we get A.D. 44.

- A threefold cord is not easily broken.

Josephus makes a casual remark to the effect that Herod died during a festival held in honour of Claudius ‘for his safety’. Claudius returned to Rome from Britain in January, A.D. 44 after an absence of six months. The festival at Caesarea, the Roman capital of Palestine, was where Herod the King died that same year. Again A.D. 44.

We can now fix the 12th Chapter of Acts down upon the calendar of the world (see chart opposite).

The year of the Crucifixion of the Lord is now accepted as A.D. 29 which is the year of the opening chapter of Acts. We have therefore the date of the first twelve chapters A.D 29-44.

Let us now seek evidence to place a date for the last chapter. The narrative leaves Paul a prisoner, but residing in his own hired house for two years, receiving all who came, teaching them freely and without reserve, ‘no man forbidding him’. These closing words of the Acts indicate a period wherein the Roman Power was tolerant to the new sect. Indeed, throughout the Acts up to the closing chapter, the Roman Government is seen in a favourable light, the persecutions detailed in the narrative coming from the Jews.

The great fire which broke out in Rome took place on July 19th. A.D. 64. If we have any knowledge at all of the awful persecution of the Christians which immediately followed, we shall find it impossible to conceive of Paul remaining unmolested in his own hired house while his followers and converts were being burned as torches or thrown to the lions. A.D. 64, therefore, is the furthest bound of the story of the Acts. It is not necessary that the Acts reaches so far, but it is practically certain that it does not extend beyond.

Paul was brought into close touch with several Roman rulers upon the occasion of his imprisonment. Let us see whether we can find another date similar to A.D. 44. The apostle was arrested at Jerusalem, sent to Caesarea, imprisoned by Felix and detained by him for two years. Felix was succeeded by Festus, who heard Paul’s defence, as did also King Agrippa. Felix was Procurator of Jud -a in A.D. 52 or 53 (Jos. Ant. xx: 7,1; Bell. Jud. ii: l2,8). Eusebius assigns A.D. 51 as the date of his appointment (Chron. ii., p. 271). Whichever of these dates may be the true one, we know from Acts 24:10 that Felix had been ‘many years’ Procurator when Paul stood before him.

When Tertullus accused Paul before Felix, he introduced his charge with the compliment, ‘seeing that by thee we enjoy great quietness’, as though this were an outstanding feature of Felix’s administration. This also had some bearing upon the nature of the charge brought against Paul. When Paul was delivered from the Jewish mob by Roman soldiers, it is evident from the words of the chief captain that he had been mistaken for the false prophet, an Egyptian who led 30,000 fanatical Jews to the Mount of Olives to see Jerusalem fall. Felix routed them, but the Egyptian had escaped. As another small link the word ‘murderers’ in Acts 21:38 is in the original sikarion. Now Josephus tells us of these sicarii who murdered people in broad daylight, and that they arose during the reign of Nero. Nero began his reign, October 13th, A.D. 54.

The ‘great quietness’ referred to by Tertullus ensued upon the capture of Eleazer, and upon his being sent to Rome after twenty years’ defiance and rebellion, and also upon the rout of the false prophet - the Egyptian for whom Paul was mistaken by Claudius Lysias, the chief captain. The numerous events that go to make up the administration of Felix fully account for three years. These, added to the earliest possible date of the ‘sicarii’, would bring us to A.D. 57. Paul arrived some time after this date, for the Egyptian had been routed ‘before these days’.

Felix was recalled to Rome to answer charges of misrule; and he was followed by accusing Jews. It was for this reason he left Paul bound, ‘willing to show the Jews a pleasure’ (Acts 24:27). Josephus tells us that Felix was saved from the due punishment of his deeds by the intervention of his brother Pallas. Now Pallas died A.D. 62 (Tacit. Ann. xiv. 65); therefore Felix must have been recalled not later than A.D. 61 in order to arrive in Rome in time for his brother’s influence to have been of any avail.

Another clue is given by a note of Josephus, that a dispute arose between Festus and the Jews, and that the Jewish deputation was considerably helped by the influence of Nero’s wife Poppoea, who was married to him in A.D. 62. Yet one more testimony. When Paul arrived at Rome he was delivered into the custody of the prefect of the ‘praetorian guard’ to strato pedarche (Acts 28:16).

The minute accuracy of Scripture enables us to fix another boundary line. One prefect is mentioned here. In A.D 62 two Prefects were appointed, Burrhus holding that office singly up to the time of his death, February, A.D. 62. We know that Paul wintered at Malta (Acts 28:1-11); the sea was not open to navigation until February, and consequently Burrhus would have been dead before Paul reached Rome, if we make his arrival as late as A.D. 62. We must therefore put it back to A.D. 61 as the latest date. Some time after the Fast, which was September 24th (if in A.D. 60), we find the apostle at Fairhavens. This places the embarkation of Paul (Acts 27:2) as about August of a year not later than A.D. 60. We have already seen that somewhere between A.D. 57 and 58 must be placed the latest date of his arrest.

Many expositors of note have unhesitatingly placed the date of Paul’s embarkation for Rome as A.D. 60. One later testimony, however, must be heard before we reach our conclusion. The testimony of Eusebius must not be lightly set aside; and Harnack, accepting his dates, places the embarkation of Paul at A.D. 56. C. H. Turner subjected the problem to a careful examination, and brings the date forward to A.D. 58. The solution he suggests is that Eusebius, in making out his calendar, could not be continually commencing a fresh year at the month in which each new king ascended the throne: and as he commenced his year with September, the first regnal year of an Emperor was dated from the September next after his actual succession. C.H. Turner reckons A.D. 58 for Paul’s trial before Festus and Agrippa.

lt will be seen that while there is a little uncertainty as to the precise date, there are certain limits beyond which it

cannot be placed. If we accept A.D. 60 for the embarkation for Rome, this will mean that Paul was liberated in the

spring of A.D. 63, and was therefore free of Rome before the fierce persecution broke out. If we accept the earlier

date, A.D. 58, Paul would have been liberated in A.D. 61, and would have had time to revisit the churches, and upon

the outbreak of the persecution under Nero he would have become involved, and would have been apprehended, this

time to seal his testimony with his blood.

We have therefore the following approximate dates:

| Acts 1,2 | A.D. 29 |

The date of the Crucifixion and of Pentecost. |

| Acts 3-11 Acts 12 Acts 13-20 |

A.D. 44 |

The date of Herod’s death. |

| Acts 21 Acts 22-27 |

A.D. 56 or A.D. 58 |

The date of Paul’s arrest at Jerusalem. |

| Acts 28 | A.D. 59 or A.D. 61 |

The date of Paul’s arrival at Rome. |

| Acts 28 | A.D. 61 or A.D. 63 |

The date of the conclusion of the ‘two years’. |

One or two details will suffice to fill in the spaces. Aquila and Priscilla were banished from Rome by the edict of Claudius, who reigned A.D. 41-54, and these dates are the extreme boundaries of Aquila’s visit to Corinth. Tacitus tells us that in A.D. 52 the Jews were commanded to leave Rome. Suetonius says, ‘Judaeos impulsore Chresto assidue tumultuantes Roma expulit’. Chrestos is by some considered as a reading for Christos. If Aquila reached Corinth at the beginning of February *, A.D. 52, Paul would have arrived a little later in the year. Acts 18:11 tells us that the apostle remained in Corinth for one year and six months; hence his departure from Corinth would be August, A.D. 53.

* Much evidence as to this and other details has been omitted as too bulky and non-essential.

Luke passes on to tell us of an incident that occurred ‘certain days’ (Acts 18:18, A.V. ‘a good while’) before Paul left Corinth, ‘when Gallio was the deputy (proconsul) of Achaia’. Incidentally we remark the exactness of Luke’s language. Achaia had been proconsular under Augustus, but had changed to an Imperial Province under Tiberius (Tacit. Ann. 1:76). It was restored again by Claudius to the Senate, became proconsular after A.D. 44, and became free under Nero. Luke never makes a mistake amid all these political changes. He had indeed ‘perfect understanding from above’. We have suggested that Paul left Corinth August, A.D. 53, so if we deduct the ‘certain days’ of verse 18, we can say that the Gallio incident was about midsummer of that year.

Claudius had appointed Marcus Ann -us Novatus to be proconsul of Achaia, this man having been adopted by the rhetorician Lucius Junius Ann -us Gallio, by which name he was known. Gallio’s brother was the famous stoic, Seneca. Now Seneca had been banished, but had been recalled in A.D. 49, and in A.D. 53 he was in the height of his popularity. Gallio was not in Achaia in A.D. 54 (Dion. ix: 35); hence A.D. 53 is the latest date in which Paul could have been brought before him, and eighteen months before this would bring us to the year 52.

Upon leaving Corinth, Paul sailed to Syria, intending to arrive at Jerusalem for the feast (Acts 18:21) which

would be Tabernacles, September 16th, A.D. 53. After the visit to Jerusalem alluded to in verse 22, the apostle went

down to Antioch and from thence ‘he went over all the country of Galatia and Phrygia in order’. This would bring

us to the spring of A.D. 54. Paul now passed to Ephesus (Acts 19:1) and remained there for the space of three years

(Acts 20:31). As he had promised to return after the feast, he doubtless arrived at Ephesus in the spring of A.D. 54.

It will be seen that a whole series of events revolves around this approximate date, and helps us to feel that we are

not very far from the truth. Another incidental note is introduced by the reference of Paul to Aretas.

The Reign of Aretas at Damascus

In 2 Corinthians 11:32 the apostle says of his humiliating departure from Damascus:

‘In Damascus the governor (ethnarch) under Aretas the king kept the city of the Damascenes with a garrison, desirous to apprehend me’.

This Aretas was the fourth of his dynasty, and reigned roughly from 9 B.C. - A.D. 40. Inscriptions are extant which speak of his 48th year, and he died somewhere between the death of Tiberius and the middle of the reign of Claudius, for his successor is found engaged in war in A.D. 48. Damascus was under Roman administration A.D. 33, 34 and A.D. 62, 63 for coins of Tiberius and Nero give no evidence of a local prince at the time. This narrows the period to somewhere after A.D. 34.

Gaius who succeeded Tiberius at this time was noted for the way in which he sought to encourage local

princelings; and it is very probable that Damascus was assigned by him to Aretas. We are at any rate shut up to A.D.

34-40, and as other calculations bring us down to A.D. 37, it appears that such a date can well be accepted.

The Famine of Acts 11:28

Agabus, a prophet of Jerusalem, foretold a famine which came to pass in the reign of Claudius Caesar. Upon this being made known, and before the famine had actually commenced, the believers at Antioch determined to send relief to Jud -a by the hands of Barnabas and Saul.

Now Josephus tells us that the famine began in the year of Herod’s death, for it took place during the government of Cuspius Fadus and Tiberius Alexander (Ant. xx. 5,2). Cuspius Fadus was appointed in the latter half of A.D. 44, and was succeeded by Tib. Alex. in A.D. 46. As Tib. Alex. was in turn succeeded by Cumanus in A.D. 50, we have a period of six years in which the famine could develop and disappear.

Premonitions of the coming dearth are evident in the care which the people of Tyre and Sidon betray to conciliate Herod. They desired peace, says Acts 12:20, ‘because their country was nourished by the king’s (Herod’s) country’. This supplies a fairly approximate date for the journey of Barnabas and Saul to Jerusalem as A.D. 44.

We have now ascertained the dating of the Acts so far as its main outlines are concerned, namely A.D. 29, 44, 60, 64. We have also found indications of the probable dates of the famine predicted by Agabus, and the apostle’s first arrival at Corinth. We will now endeavour to place the missionary journeys that were undertaken by the apostle.

Acts 13 and 14. This journey has been located somewhere between A.D. 44 to 48. C. H. Turner in Hasting’s Dictionary of the Bible, considers that eighteen months are required for this journey. Prof. Ramsay estimates two years and three or four months. Among the items that influence a conclusion must be the character of the district, the climate, and their effect upon travelling.

The hill country lying between Perga and Antioch in Pisidia, would not be crossed usually between December and March. If we therefore imagine that Paul’s itinerary would be arranged to suit the natural condition of the country, the following seems to be a possible time-table. It is the one suggested by C. H. Turner as above.

Paul arrived at Cyprus in April. Then went through the isle (Acts 13:6), and left Paphos in July, reaching Antioch in Pisidia in August. Shaking off the dust of his feet against Antioch, Paul reached Iconium in November. Here the disciples were filled with joy and with the Holy Ghost; and here also we read that Paul and Barnabas abode ‘a long time’. As it was nearing winter when they arrived, the probability is that they remained there until the Passover. By April, therefore, they would have arrived at Lystra and Derbe, and the region round about (14:6,7). They would begin the return journey about the beginning of July, reaching Pamphylia by October, and getting back to Antioch and Syria by November. We shall therefore be fairly safe to assign the years A.D. 45 to 48 for this first missionary journey.

Among the items of interest that need to be placed in their chronological order, are the visits of the apostle to

Jerusalem.

Paul’s Visits to Jerusalem

FIRST VISIT (3 years) |

Acts 9:26-30 (Gal. 1:17-21) |

Compare ‘Syria and Cilicia’, with ‘Caesarea and Tarsus’. |

SECOND VISIT (14 years) |

Acts 11:29,30 (see also 12:25) |

Before the first missionary journey. |

THIRD VISIT |

Acts 15:2-4 |

After the first missionary journey. |

FOURTH VISIT |

Acts 18:21,22 |

To keep the Feast. |

FIFTH VISIT |

Acts 21:15 to 23:30 |

Taken prisoner. |

Before we can place the epistles of Paul in their true chronological order, it will be necessary to deal with the related problem: ‘Where is Galatia?’ for when that question is settled, the chronological place of the epistle to the Galatians is easily discovered.

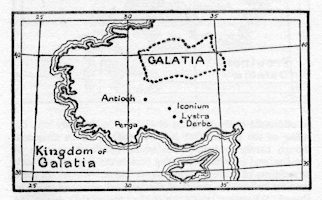

Where is Galatia? The answer to the question depends upon the date at which the map consulted was published. If the map be that of Dr. Kitto’s Cyclopaedia, 1847, or T. R. Birks, editor of Paley, 1849 or any other publication before them, Galatia will be as shown in the following map:

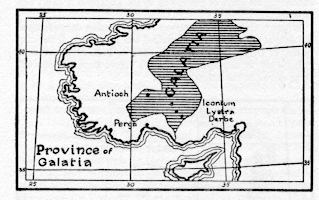

If we look at Lewin’s Life and Epistles of Paul (1875), we shall find two maps, one showing the province of Galatia with indications that national boundaries had given place to political necessities; the other showing Asia Minor mapped according to its nationalities. A comparison of the two maps will reveal a marked difference. While the national boundaries coincide with Kitto’s map, the political map reveals a state of affairs which must materially influence the answer to the question, ‘Where is Galatia?’

Upon this map are parts labelled, ‘Part of Phrygia included in the Province of Asia; Part of Phrygia in the Province of Galatia’. In Ramsay’s ‘Historical Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians’ is a map showing the political divisions of Asia Minor, A.D. 40 to 63. We give here a sketch of this, indicating the province of Galatia by shading the drawing.

It will be seen that a letter addressed to churches situated in the Phrygian portion of the Galatian province, would have to be addressed to the churches of Galatia, in harmony with the ruling of the powers that be. A pedant may be imagined, though hardly probable, who would ignore the growth of London, and address those living outside the original city walls as residents of Surrey, Middlesex, or Essex. We cannot for a moment believe the writer of the inspired narrative to be so absurd. Whatever Galatia was to the mind of the rulers of the day would settle the question for him, not withstanding that a great many nationalities were included in the one Province. Paul himself is a case in point. He was a Hebrew, a Tarsian, and a Roman. Would anyone set out to debate as to whether Tarsus was in Italy or Rome in Cilicia?

Young’s Analytical Concordance (New Edition) no longer shows Galatia according to its national limitations, but shows the larger Province of Galatia extending southward to include Derbe, Lystra, and Iconium, which had hitherto been contained in Lycaonia: so also does an Atlas illustrating the Acts of the Apostles and Epistles published by S. Philip & Sons, in 1914.

It will be seen from this transition and change, that the simple question, ‘Where is Galatia?’ does not admit of a simple answer. It will be also evident that the question is removed from purely Scriptural exposition, to that of arch -ology and history. Quoting from The Times:

‘Professor W. M. Ramsay is the greatest living authority on the geography of Asia Minor, and the historical and archaeological questions associated with its study’.

Whatever theological opinions the Professor may hold, it is surely right to hear him in this province so peculiarly his own. And as to the theological side, the Professor approached the study believing that the Acts of the Apostles was written some 200 years later than Paul’s lifetime: he concluded it by believing that Luke was the writer during the lifetime of the apostle. In other words, his investigation disproved Higher Criticism, and proved the Bible. This is decidedly encouraging.

It will be superfluous to use quotation marks in this article, for where Prof. Ramsay or his critics are not quoted, some of the expressions are bound to be reminiscent of the writings of others. Those who wish to pursue the theme more fully than can be undertaken here are recommended to the various bulky volumes from Prof. Ramsay’s pen, the able book by Mr. Askwith, and the commentary of Kirslop Lake.

Returning to the question: ‘Where is Galatia?’ and what is the meaning of the differing maps, we reply: ‘The

small district marked on the old maps as Galatia is the kingdom of Galatia.’ The larger area including the cities

visited in Acts 13 and 14 is the Roman Province of that name. To understand more fully the subject before us, we

must bear in mind that there were three classes of states in Asia Minor:

| 1. Countries incorporated in the Empire in which law was administered by a Roman Governor. | Included in the conception of the Roman world. |

| 2. Countries connected with Rome by an agreement or alliance, the terms of which were expressed by treaty, i.e., Client States according to the usual and convenient expression, among which the chief were Galatia and Cappadocia. | |

| 3. States in no formal and recognized relations with Rome, especially Pontus and the Isaurian Pirates. | Enemies. |

The Roman range of authority and action in any foreign land constituted a Provincia. Strabo shows the policy of the Romans regarding the question of small kings and Roman governors. Where the character of the people was unruly, and the nature of the country made rebellion and lawlessness easy, kings with their own standing army were placed in authority, but step by step, and district by district, these countries were incorporated in the adjacent Roman Provinces, as a certain degree of discipline and civilization was imparted to the population by these kings, who built cities and introduced the Gr -co-Roman customs and education.

As the above paragraph is appreciated, the changing of the map, and the enlarging of the borders of Galatia the Kingdom to Galatia the Province, will be understood. For convenience of reference, we divide the existing teaching on the subject into two views:

- The North Galatia view.

- The South Galatia view.

The North Galatia view maintains that only that part of the map which was originally Galatia is the Galatia of the Scriptures. It recognizes that it is somewhat awkward to have to acknowledge that of all the cities of North Galatia, which the apostle is supposed to have visited, and where he is supposed to have founded the churches, and to which he addressed his epistle, Tavium, Ancrya, Pessinus, not one is even mentioned in the Acts.

The South Galatia view maintains that by Galatia is intended the Galatia of the day, the large Roman Province which had embraced Lycaonia and part of Phrygia on the south. According to this view, every city is named, and Antioch, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe are seen as the churches of Galatia.

The North Galatia view necessitates that the epistle to the Galatians was written after Acts 18:23, for Galatians 4:13 indicates a second visit. This associates ‘Galatians’ with ‘Corinthians’. The South Galatia view sees no necessity for a later date.

While Acts 16:6 is looked upon by the North Galatia view as the first mention and founding of the church of Galatia, giving no names or incidents of the journey, the South Galatia view looks upon Acts 16:6 as a re-visiting of the churches already founded in Acts 13 and 14; and the brief summary is most fitting and understandable. Full details had already been given in Acts 13 to 15.

Before passing on in our study, we will give historic proofs that Iconium, Lystra, Derbe and Antioch are rightly addressed as ‘Galatia’:

- Asterius, Bishop of Amaseia in Pontus, A.D. 401, in dealing with Acts 18:23 explains it in direct contradiction of what was true in his own day. Lycaonia was not included in Galatia in A.D. 401.

- Dr. Schurer retracted his criticism of Prof. Ramsay’s position after consulting Pliny and Ptolemy. Ptolemy

arranged his chapters according to the Roman Proconsular divisions:

v. 1. Pontou kai Bithunias Thesis.

v. 2. Tes idias Asias Thesis.

v. 3. Lukias Thesis.

v. 4. Galatias Thesis.

‘No conceivable interpretation could get Lycaonia out of Galatiken choran except deliberate adhesion to the South Galatian view’.

He states that Galatia is bounded on the South by Pamphylia, and on the north by the Euxine Sea, including in it Pisidia in the south, and Paphlagonia in the north. He enumerates parts of which it consisted, and mentions Antioch, Iconium, and Lystra as cities of Galatia.

So far as the date of the epistle is concerned, it has been assigned by different critics to the close, and to every intermediate stage, of its author’s epistolary activity. Marcion places ‘Galatians’ first. Accepting as we do the teaching that Antioch, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe are the churches of Galatia, the necessity for placing the writing of the epistle to a period subsequent to Acts 18:23 is entirely removed. Both Ramsay and Weber believe that ‘Galatians’ was written from Antioch. Ramsay views Acts 13 and Acts 16 as the two visits; Weber considers that the outward and homeward journeys of 13 and 14 suffice.

It is strange that Paul makes no reference to the ‘Decrees’ in Galatians, and this silence is taken as an indication that the epistle was written before Acts 15. Further, it has been said, the Judaizers could hardly ‘compel’ circumcision (6:12), after the decision at Jerusalem (Acts 15). Peter’s action in Galatians 2 is also much more difficult to understand if after Acts 15. Altogether, everything is favourable to an early date for the epistle, and we believe we shall not be wrong in placing it first in chronological order.

Since writing this chapter, the author has come across a small book (The Date of Galatians, by Douglas Round), dealing with the date of the epistle, in which the writer, while accepting the South Galatian view of Prof. Ramsay, does not accept the date suggested by him, but argues very strongly for the position which we have felt to be the true one, namely, the earliest of all the epistles. We quote his own opening words:

‘Before the appearance of his (Prof. Ramsay’s) books setting out the South Galatian theory, the epistle to the Galatians seemed to be in the air, and to have no relation to the Acts of the Apostles or to any other writing. His brilliant work illuminated what had been before a dark corner. The interest so aroused led me to study the subject more closely, and eventually to form the opinion expressed in these pages, as to the earlier date of the epistle. The later date was the burden laid by necessity upon the holders of the North Galatian theory. Prof. Ramsay might have cast off the burden so inherited. Instead of so doing, he gratuitously (as it seems to me) tied the burden round his neck to the great injury of the South Galatian theory’. *

* In a review of the first edition of this Analysis, F.F. Bruce pointed out ‘... that in his later works (The 14th edition (1920) of St. Paul the Traveller, pp. 22-31) Sir William Ramsay did accept the view expressed here, that Galatians is the earliest of the extant Pauline letters’.

Without going through all the controversy raised in this book, we give the following summary of the essential

points:

-

Was the epistle written before or after Acts 15?

- The private conference of Galatians 2 took place upon the second visit of the apostle to Jerusalem, which was

that of Acts 11:30. The reference to ‘the poor’, and Paul’s expressed readiness, coincide with the errand of

mercy mentioned in Acts 11:30.

- After the private conference at Jerusalem, Peter dissembles at Antioch. The question at issue at Antioch was

not, ‘should the Gentiles be circumcised’? that had been settled; but, ‘should the circumcised eat with the

uncircumcised?’ On this point Peter wavered. Peter felt the force of the rebuke, and acted accordingly at the

public Council (Acts 15).

- Paul paid the Galatian churches two visits (Acts 13). The return visit was important. The faith which the

apostle had preached (13:39), they were exhorted to ‘continue in’ (14:22), and the persecution which they

knew the apostle suffered (13:50), was a part of their expectation also - ‘we must through much tribulation

enter the kingdom of God’.

- While the apostle abode at Antioch for ‘a long time’ some of the emissaries from Jerusalem went on to

Galatia. The result of their visit is recorded in Galatians 1:6. Paul at once, from Antioch, and just before the

conference (Acts 15), wrote the epistle.

- The contention which necessitated the conference necessitated also the epistle.

- The decrees, formulated by the Council, are never mentioned in the epistle. If the Apostle had received

them, he would be obliged in all honesty, to have said so. Further, the fact that these decrees practically

endorsed the exemption of the Gentiles from the Law was a strong argument for the apostle. If the epistle

had been written after Acts 15, would not the apostle have settled the question at once by reference to the

decrees?

In the epistle we can have no doubt the apostle uses the strongest arguments that at the time of writing were possible. The close connection between Acts 13 and the epistle is also an argument for nearness in point of time. He argues in the epistle as though his teaching would be still clearly remembered.

Galatians 4:20 suggests a desire to revisit them. Why did he not go? The simple reason was that he was obliged to go up to Jerusalem for the conference instead.

Douglas Round’s own summary is as follows:

- By this view no visit of Paul to Jerusalem is suppressed.

- The most forcible arguments that could be used at the time are used.

- No inconsistency is intruded into the Acts.

- Every phrase which bears upon the date is simply and naturally explained.

- The authority of the Council at Jerusalem, and the decree made, remains unimpaired.

- The epistle was written from Antioch or the neighbourhood.

- The churches of Galatia were those of Pisidia, Antioch, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe.

- The epistle is probably the earliest book in the New Testament.

Having established the position of the epistle to the Galatians, we can now set out the chronology of the Acts and

the place of the epistles, with some measure of assurance that, while every detail cannot be proved, and a margin of

one or two years must be permitted, yet for all practical purposes, the following calendar can be accepted with every

confidence. The external history recorded in the Acts, keeps pace with the internal revelation of doctrinal and

dispensational truth recorded in the epistles, and this relationship we now indicate by pointing out a few of the

verbal links that associate an epistle with its place in the Acts. We take as our basis of comparison Paul’s own

summary given in Acts 20:18-21.

The relation of the epistle with the Acts |

|

ACTS |

EPISTLE. |

| ‘After what manner I have been with you’ (Acts 20:18). | ‘Ye know what manner of men we were among you for your sake’ (1 Thess. 1:5). |

| ‘Serving the Lord’ (Acts 20:19). With the exception of the statement of our Lord Himself, ‘Ye cannot serve God and Mammon’ douleuo is used exclusively by the apostle for service unto the Lord. There are six occurrences in his epistles which, together with Acts 20:19, make seven in all. | ‘Fervent in spirit; serving the Lord’ (Rom. 12:11 and see also Rom. 14:18; 16:18; Eph. 6:7; Col. 3:24 and 1 Thess. 1:9). |

| ‘Serving the Lord with all humility of mind’ (Acts 20:19). | ‘In lowliness of mind let each esteem other’ (Phil. 2:3). Paul is responsible for six out of the total seven occurrences of tapeinophrosune, ‘humility of mind’. |

| ‘With many tears, and temptations’ (Acts 20:19). | ‘My temptation which was in my flesh’ (Gal. 4:14). |

| ‘How I kept back nothing that was profitable’ (Acts 20:20). | ‘But if any man draw back’ (Heb. 10:38). |

| ‘How I kept back nothing that was profitable’ (Acts 20:20). | ‘All things are not expedient’ (1 Cor. 6:12). There are sixteen occurrences of sumphero ‘expedient’ or ‘profitable’ in the New Testament: eight occur in the Gospels and Acts 19:19, and the other eight exclusively in Paul’s epistles. |

| ‘The Holy Ghost witnesseth in every city’ (Acts 20:23). | ‘The Spirit itself beareth witness with our spirit’ (Rom. 8:16). |

| ‘That I might finish my course’ (Acts 20:24). | ‘I have finished my course’ (2 Tim. 4:7). These are the only occurrences of dromos ‘course’ except that in Acts 13:25, where, again, Paul is speaking. The use of the verb teleioo, ‘to perfect’, in the sense of finishing a race, is characteristic of the apostle’s language, especially in Philippians 3 and the epistle to the Hebrews. |

| ‘Over the which the Holy Ghost hath made you (tithemi) overseers’ (Acts 20:28). | ‘Whereunto I am appointed (tithemi) a preacher’ (2 Tim. 1:11). |

| ‘Not sparing the flock’ (Acts 20:29). | ‘If God spared not the natural branches’ (Rom. 11:21). There are seven occurrences of pheidomai, ‘to spare’ in Paul’s epistles. Elsewhere it is found only in Acts 20:29 or 2 Pet. 2:4,5. |

| ‘Therefore watch, and remember’ (Acts 20:31). | ‘For ye remember, brethren, our labour’ (1 Thess. 2.9). Mnemoneuo. - This is a word very characteristic of the apostle Paul. He uses it again in Acts 20:35, seven times in the Church epistles and three times in Hebrews. |

| ‘Therefore ... remember ... night and day’ (Acts 20.31). | ‘With labour and travail night and day’ (2 Thess. 3:8). The association of night and day as an indication of continuance is a characteristic expression of Paul. He uses the combination seven times (Acts 26.7; 1 Thess. 2:9; 3:10; 2 Thess. 3:8; 1 Tim. 5:5; 2 Tim. 1:3). The other epistles do not use the expression. |

| ‘I ceased not to warn every one’ (Acts 20:31). | ‘Warning every man, and teaching every man’ (Col. 1:28). This word noutheteo, ‘to warn’, occurs in seven passages, all of them in Paul’s epistles. It occurs nowhere else except in Acts 20:31, where it is Paul who is speaking. |

| ‘An inheritance among all them which are sanctified’ (Acts 20:32). | ‘The inheritance of the saints in light’ (Col. 1:12). |

| ‘I have coveted no man’s silver, or gold, or apparel’ (Acts 20:33). | ‘Neither ... used we ... a cloke of covetousness’ (1 Thess. 2:5). This is a characteristic attitude of the apostle Paul. |

| ‘These hands have ministered unto my necessities’ (Acts 20:34). | ‘We labour, working with our own hands’ (1 Cor. 4:12). |

| ‘These hands have ministered unto my necessities’ (Acts 20:34). | ‘Distributing to the necessity of saints’ (Rom. 12:13). |

| ‘These hands’; ‘These bonds’ (Acts 20:34; 26:29). ‘How that so labouring ye ought to support the weak’ (Acts 20:35). | ‘We both labour and suffer reproach’ (1 Tim. 4:10). Kopiao, ‘to labour’ is a word much used by the apostle. He employs it fourteen times in his epistles. None of the other apostles use the word except John (Rev. 2:3). |

Here, within the compass of eighteen verses, we have eighteen instances of the usage of words peculiarly Pauline. Could there be more convincing proof that Luke is a faithful eye-witness, and a trustworthy historian?

We conclude this analysis by setting out the chronological order of the fourteen epistles of Paul.

Chronological Order of Paul’s Epistles

Seven Epistles before Acts 28

GALATIANS. ‘The just shall live by FAITH’ (Gal. 3:11).

1 THESSALONIANS. ‘Faith, Hope and Love’.

2 THESSALONIANS. Written to correct erroneous views arising out of first epistle and emphasizing Satanic counterfeit (2 Thess. 2).

HEBREWS. ‘The just shall LIVE by faith’ (Heb. 10:38).

1 CORINTHIANS. ‘Faith, Hope and Charity’ - these ‘abide’.

2 CORINTHIANS. Written to correct erroneous views arising out of the first epistle, and emphasizing Satanic counterfeit (2 Cor. 11).

ROMANS. ‘The JUST shall live by faith’ (Rom. 1:17).

The hope of Israel is in view from Acts 1:6 to Acts 28:20. It appears in Acts 26:6,7, Romans 15:12,13 and

1 Thessalonians 4:15-18. All reference to ‘The twelve tribes’, ‘The reign over the Gentiles’ and the ‘Archangel’

cease at Acts 28:28. With the setting aside of Israel a new dispensation comes into operation, and a new set of

epistles.

Seven Epistles after Acts 28

EPHESIANS. The revelation of the Mystery.

PHILIPPIANS. Bishops and Deacons. The Prize.

PHILEMON. Truth in practice.

COLOSSIANS. The revelation of the Mystery.

1 TIMOTHY. Bishops and Deacons.

TITUS.

2 TIMOTHY. The Crown.

The evidences for the exact dating of these Prison and Pastoral Epistles are not sufficient to enable anyone to dogmatize. All that we feel can be said with some measure of confidence is, that 1 Timothy and Titus were written in the interval of freedom that intervened between the two years at Rome (Acts 28:30), when Paul was treated as a military prisoner and allowed some measure of liberty, and the subsequent imprisonment when he was treated as an ‘evil doer’, and from which there was no hope entertained of release, except by death.

Most students know that it is necessary to antedate the birth of Christ by a few years, some say three, some four,

some five. The Companion Bible makes the date of the Nativity 4 B.C., and the date of the Crucifixion A.D. 29. The

Lord commenced His public ministry when He was ‘about thirty years old’ and this ministry continued for a space

of three years and a half. This means that the date of the Crucifixion must be somewhere round about A.D. 29, but

the reader will see from the following chronology that, working back from the settled date of Acts 12, 13, A.D. 44,

we have felt obliged to adopt A.D. 30. We do not attempt to supply actual details, until we arrive at A.D. 36, the date

of Saul’s conversion. The calendar travels beyond the end of the Acts which we have put as A.D. 63, adding two

more years to complete the apostle’s ministry. To this we add five more years to bring us to the date of the

destruction of Jerusalem. It will be observed that from A.D. 30 to A.D. 65 we have a period of thirty-five years, or

five sets of seven years, each seventh year being marked by a Divinely expressed comment. Thirtythree whole years

of the Saviour’s life are balanced by thirtythree whole years of His ascended ministry ‘The Lord working with

them’, which period also is the length of time which David reigned over all Israel (2 Sam. 5:5). The dates of the

epistles are indicated, together with the several journeys of the apostle to Jerusalem, and other matters of interest

concerning the dates of which some measure of exactness is possible are tabulated:

Chronology of Acts 9 to 28 |

||||

Event |

Chapter |

Year |

Event |

Epistle |

| 31 | ||||

| 32 | ||||

| 33 | ||||

| 34 | ||||

| 35 | ||||

| 9 | 36 | Paul converted | ||

7. ‘Rest’ |

9:31 | 37 | ||

| ARETAS | 38 | 1st Jerusalem | ||

| 39 | ||||

| 40 | ||||

| 41 | ||||

|

42 | |||

| 11:26 | 43 | Christians | ||

Famine 7. ‘Growth’ |

11:28 12:24 |

44 | ||

| 45 | 2nd Jerusalem | |||

| 12:1 | 46 | 1st Mission | ||

| Cyprus (April) | 47 | |||

| Return (July?) | 48 | Antioch (Nov.?) | ||

| 49 | ||||

| 50 | 3rd Jerusalem | |||

7. ‘Increase’ |

16:5 | 51 | 2nd Mission | Galatians |

| FELIX Jews |

18 | 52 | Gallio | 1 and 2 Thess. |

| Expelled 18 months Death of CLAUDIUS |

53 | Feast Sept. 16th | Hebrews | |

| Ephesus | 19:1 | 54 | 4th Jerusalem | |

| 19:21 | 55 | 3rd Mission | ||

| 3 years | 20:31 | 56 | ||

| 57 | ||||

7. ‘Arrest’ |

22: | 58 | 5th Jerusalem | 1 and 2 Corinthians |

| 59 | 2 years prison in Caesarea |

Romans | ||

| FESTUS | 24:27 | 60 | ||

| 61 | ||||

| 28: | 62 | 2 years prison in Rome |

MYSTERY made known |

|

| End of Acts | 63 | |||

| Fire at Rome | Nero | 64 | Spain and the West | 1 Timothy and Titus |

7. ‘Finished’ |

2 Tim. 4 | 65 | Evil doer | 2 Timothy |

Two dates, namely A.D. 44, the death of Herod (Acts 12:23) and the fire of Rome, A.D. 64, peg the Acts down upon the calendar of the world, the rest is a matter either of arithmetic or of careful reading and comparison. As we said at the beginning of this article, some datings must remain tentative, but for all practical purposes the above chronology will prove to fit the circumstances and give a faithful all-over picture of the whole of the apostle’s ministry.

Home | About LW | Site Map | LW Publications | Search

Developed by ©

Levend Water All rights reserved